Haiti is one of our nation’s nearest neighbors, and has been a key player in world history over the past 200 years. The Haitian revolution took nearly 15 years and cost countless lives, but resulted in one of the first nations that was slave-free and ruled by non-whites and former captives. The loss of Haiti (then called Saint-Domingue) forced the cash-starved Napoleon to sell the Louisiana territory to the United States, one of the single largest land purchases in our countries history. In the ensuing 200 years, Haiti has struggled; as a country founded by former slaves, they were forced to repay reparations for lost ‘property’ to France (approximately $21 Billion, according to Wikipedia). And recent comments by a world leader suggests that their struggle are far from over. Despite ALL of this, I (personally) knew nearly next to nothing about Haiti prior to a year ago. While I would periodically hear about tragedies like the 2010 Hatian earthquake and the subsequent cholera epidemic (that the UN only recently took responsibility for), Haiti always remained … ‘over there’ in my mind. A place that exists, that I may have learned about, but was never quite close enough for me to think much about.

Luckily, Garrett Lab and University of Florida are involved in a rather large Feed the Future AREA project focused on improving Haitian agriculture, and I have learned a lot more in the past year. My labmember Dr. Joubert Fayette is a Haitian national who got his PhD here at the UF Plant Pathology department, and is working to help re-build the diagnostic capabilities of Haiti so that they can detect and respond to threats (you can read more about his work with AREA here). Wanita Dantes and James Fulton are graduate students in garrett lab researching an emerging plantain disease in Haiti that causes the trees to topple over just as they are full of fruit. While my work primarily focuses on laurel wilt disease of avocados in Florida, Haiti and Dominican Republic are some of our nearest neighbors, so we wanted to get an initial look at how at-risk their avocado groves are to Laurel Wilt Disease. We wanted to find some production statistics that might help to explain where production occurs in the country and where we should be monitoring for disease. We were also curious about production statistics for other crops: other projects in Garrett lab focus on a disease that alternatively hosts on mango, and sweetpotato seed trade in Uganda (see more of Kelsey Andersen’s work here).

The Data

I found a dataset of a report posted by the Haitian Ministry of Agriculture (see it here (PDF WARNING)). The report is in French, but I took a few years of french in high school and my grandfather and mother speak french, so I was able to piece together enough. The report describes different levels of production of some important crops in Haiti in different Departments (effectively like states). I got map data of the different Departments from (GADM)[https://gadm.org/maps.html], which hosts maps of political boundaries at different levels (country, state, county, town).

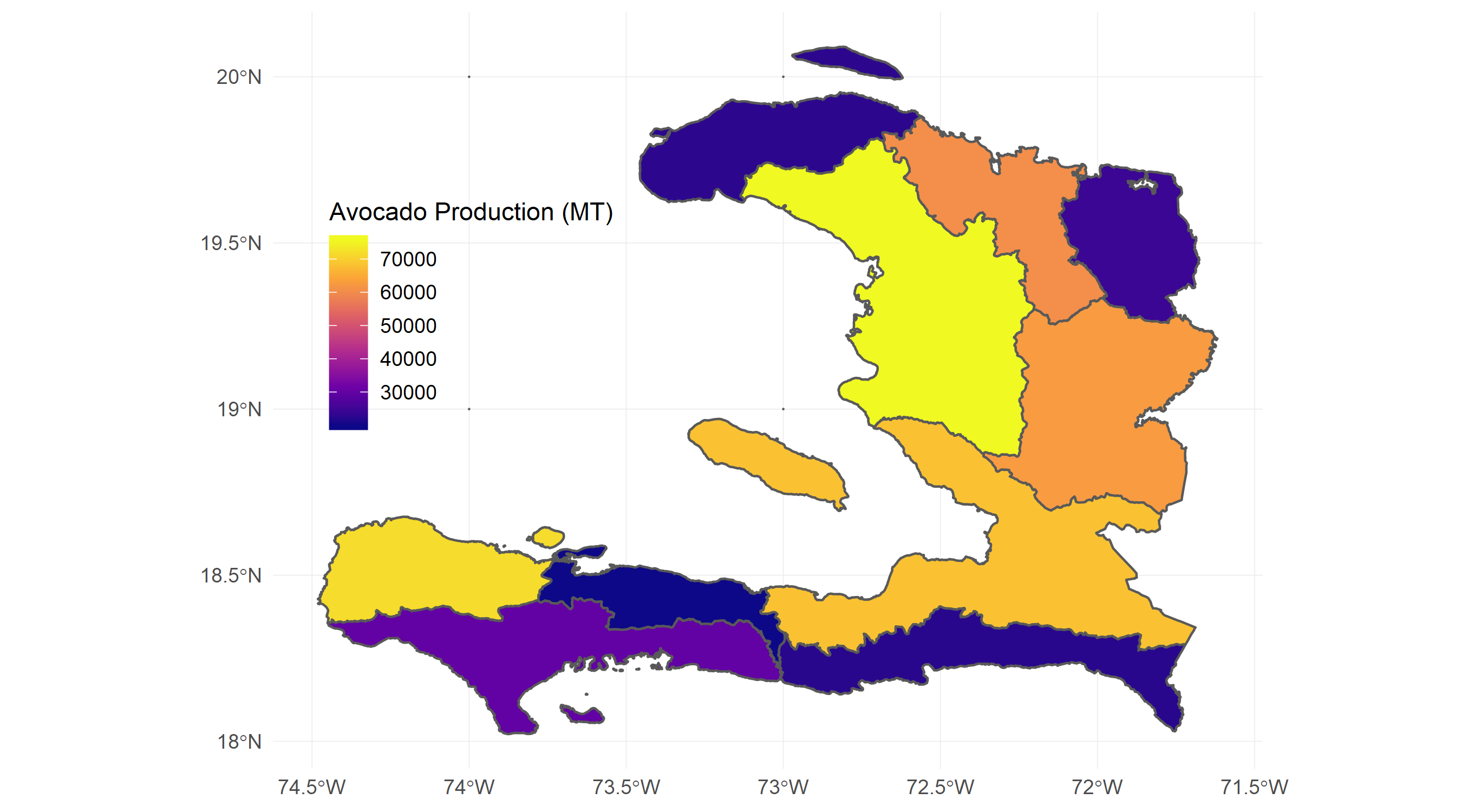

Avocado Production

I was primarily concerned about finding out more about avocado production in Haiti. Avocado production in Haiti and the Dominican Republic are important both for local and export markets, as well as for food security. Most of the fruit are West Indian types, which are typically greener, and have a less buttery feel to them than Hass varieties. We grow a ton (~8000 acres) of West Indian varieties, and Dominican Republic is our main market competitors. Many of the varieties that are in Haiti were brought there from California and Florida in the mid-1920’s to the Central Experiment Station of the Hatian Dept. of Ag. near Port au Prince.

This map shows some fairly heavy production in the Artibonite and Grand-Anse regions as well as in the Nord and Centre Departments. We now need to locate important agricultural ports and run some wind run models to see what is the liklihood of the disease reaching these areas. That is for a future publication

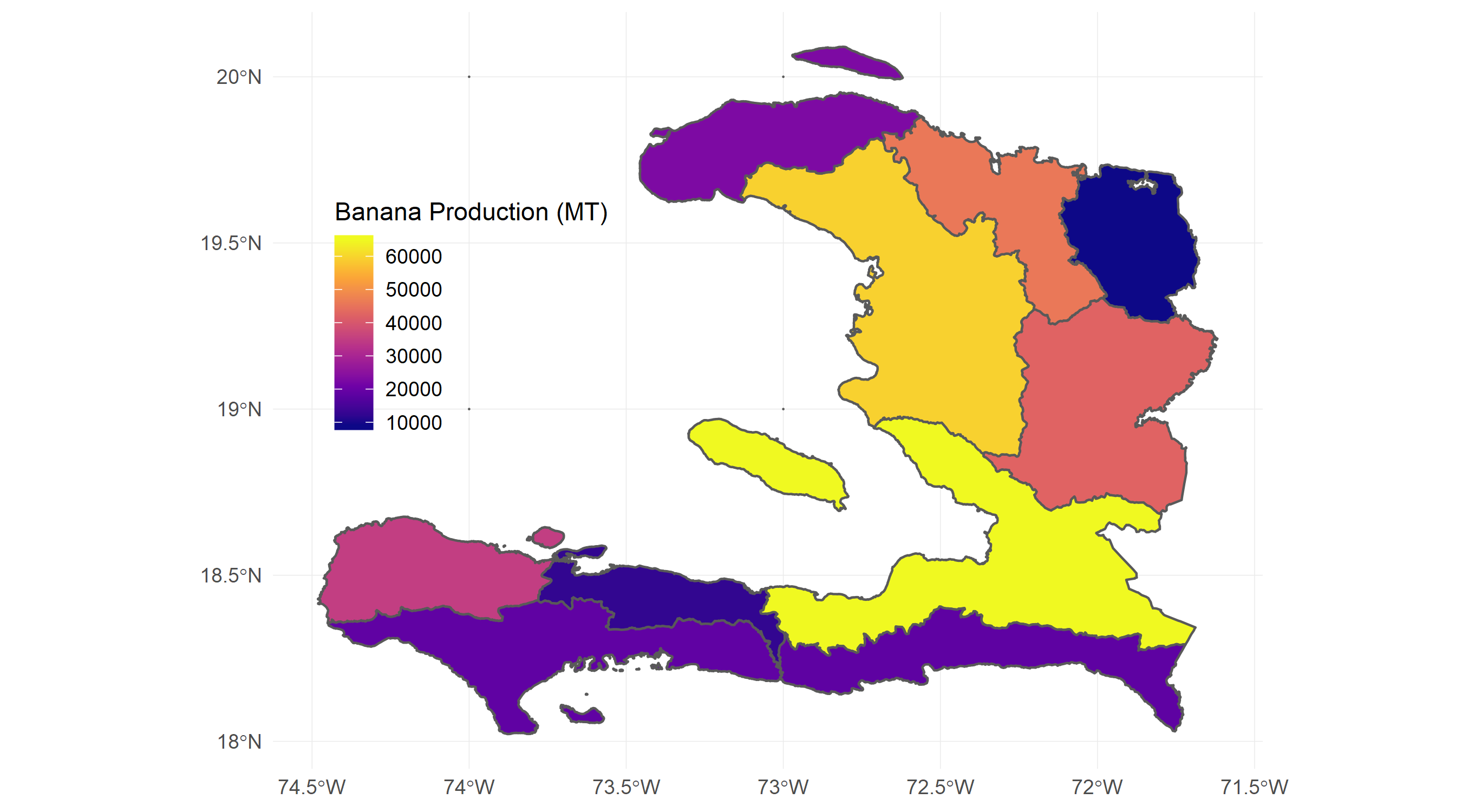

Banana and Plantain Production

We were interested in banana and plantain production because of Toppling disease, and it looks (based on this map) like much of the production is in the Ouest Department. We are currently comparing these data to other published data to see if it matches with what has previously been reported for banana production.

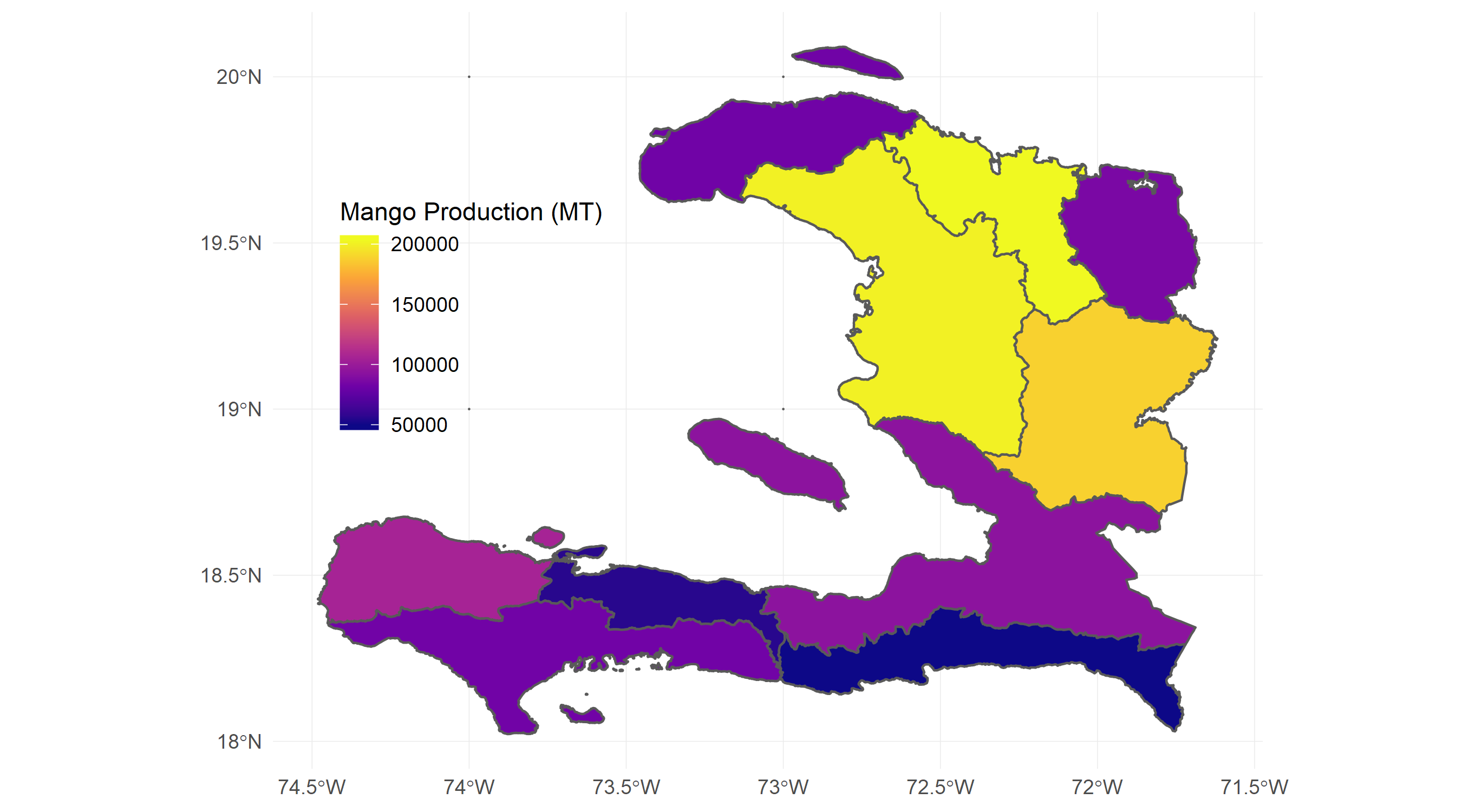

Mango Production

Mangos are incredibly delicious (see my previous blogpost if you don’t believe me!), and are both nutritionally and economically important for Haiti.

Most of Haitian mango production is in the Artibonite and Nord Departments.

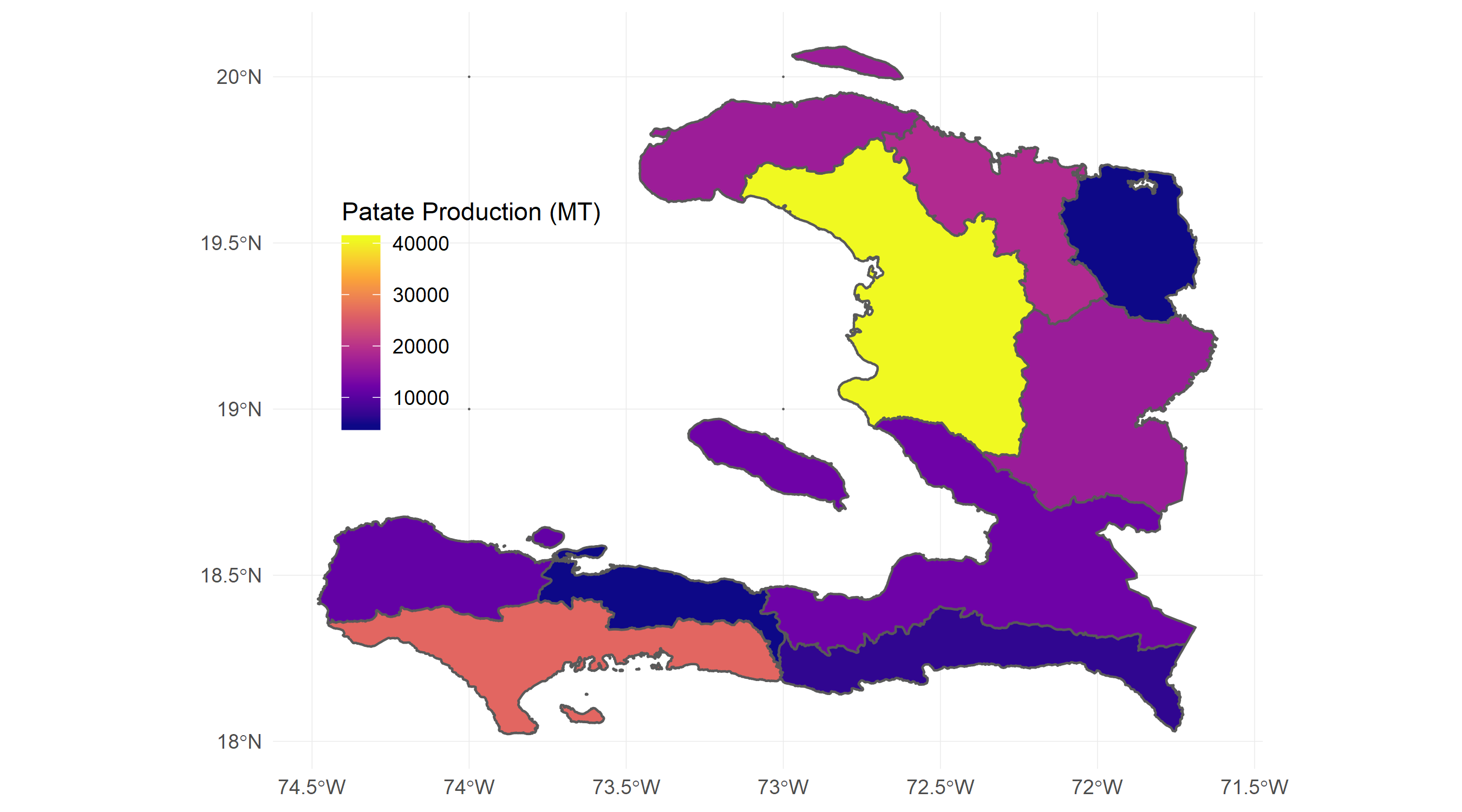

Sweetpotato Production

Sweetpotatoes were the trickiest. The Haitian word, ‘patate’ sounds VERY close to potato; luckily Joubert corrected my rookie mistake!

Like many of the other crops here, there is heavy production in Arbonite Department.

Conclusions

Haiti is an incredibly resilient country that just needs a little bit of help to make it’s agriculture robust and sustainable. I am fortunate to work alongside those involved in the AREA project as they help to rebuild this proud country’s capabilities for sustainable agriculture!